|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first step that king Gagik took was to make himself recognised as king by the two foreign superpowers Arabs and Byzantines, and to direct the country towards a system of centralised government, subjecting the various dominations to his rule. In this field, strong supported by the popular and peasant masses, who revealed in the kings person their hopes of liberation from exploitation and tyranny of the other feuds, Gagik succeeds in realising his aims and creates a national army, a corps of guards formed by noble officers linked to the court, makes the crown hereditary, creates an independent KatholikÚs from that of Dvin, imposes the elected KatholikÚs to belong to the royal family, and places his officials and officers everywhere. With the mirage of large compensations he lures to the court, following also the footsteps already made by the court of Baghdad and drawing example from local tradition, numerous technocrats, bureaucrats, philosophers, scientists, poets and architects.

Under Gagik's rule Van does not remain the capital for long; Vostan soon substitutes it, not far from lake Van (altitude 1720 m.). Almost in front of it is the island of Akdamar. The new capital is encircled by numerous towers and ponderous walls, but of them, as of its most beautiful palaces and of the church of. St. Astvatzatzin, not a trace remains, following disastrous destruction during the XV century. Vostan, owing to its position is not easily defendable: that is why the capital was changed to the island of Akdamar (Lake of the vishap = dragons) well defended by the waters of the lake. The island from the IV century presents a fortified complex, where the rulers of the locality, the Rshtouni, took shelter in case of necessity. It was also used as a slave-clearing centre. At the end of the IX century various areas were recovered by means of dams and successively filled in, the building industry was mobilised and the task was assigned to an architect called Manuel. He became responsible for all the constructions while an enormous quantities of stone (pumice stone, volcanic rock) were transported from the mainland to the island, in particular from the fortress of Kotom (south-west of the lake of, Van), raised to the ground by King Gagik. In a short time the island became a true fortified city, and successively developed as the royal residential nucleus. During the XI-XII centuries it becomes a monastery and residential centre of the KatholikÚs of the Vaspourakan region. Akdamar becomes seat and capital of the Artzrouni, flourishing and prosperous, full of palaces, among which is the residential palace of king Gagik, quarters for the royal guard and the court, with a school, a church, public and private offices, stores and a prison. With the exception of the church of the Holy Cross, nothing remains of the sumptuous royal palace of Gagik or the minor buildings (the state treasury, the armoury and stores), nearly all the work of Manuel. The church of the Holy Cross at Akdamar belongs to the large family of central-plan buildings which for entire centuries represented, with numerous interpretations and elaborations, the privileged form in which sacred architecture was expressed everywhere; particular in the East and more specifically in Armenia where it richly flowered from the VI century onwards. From the primitive complex at Avan (VI-VII centuries) one passes to the form of the church of St. Hripsimť at Vagharshapat (a tetra-cone with four apses each placed on the main axes, four niches on the diagonal axes and four rooms, one on each corner), which was to become in a certain sense the reference model for this type of building, (Targmantchats in Aygeshat, St. John of Sisian, Garnahovit at Adżyaman, Aramous, Aloutchalou and finally St. Echmiatzin of Soradir). The latter was undoubtedly the model for Architect Manuel who built' the church of the Holy Cross at Akdamar. It should be noted that, even though this church relates unmistakably to the others, it is also without a doubt that it is the force with which the church at Akdamar stands out among these examples for the singularity of its' plastic form that makes it really unique - in the whole history of Art, and not only of Armenian Art. The novelty lies in the knowledge with which the architect, having abandoned the rigid traditional control of the external volume which characterised all Armenian architecture, succeeds in making the stones speak for themselves by restoring their expressive quality. The entire external decorative apparatus ceases to be such, by becoming the protagonist of a more encompassing architectural scheme where the languages of sculpture and architecture are harmoniously combined. |

|

|

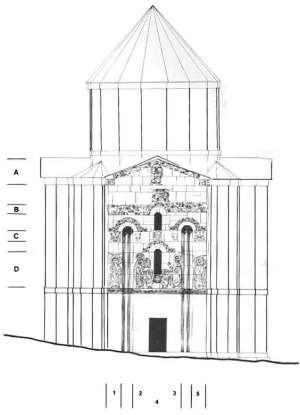

Western facade

|

| One enters the church by means of two entrances:

one on the western side and the other on the southern side but today both these entrance

are engulfed by buildings added in later centuries (the first entrance is covered by a

gavit built in 1973 and the second entrance by a small doorway-bell tower built in the XIX

century). The plan is substantially a tetra-cone with four semicircular apses, (the western and eastern apses are deeper) and four niches on the diagonals. From the two niches on the eastern side one has access to the chapels which flank the eastern apse of the church. The apses and the niches, internally terminate in semi-spherical calottes which, with relative pendatives, support the ring of the drum, the drum and the dome (7, 8, 55, 56, 57, 58): the dome is internally hemispherical and externally conical which, with intentional insistence, recalls the forms of the extremely high surrounding peaks. The long and narrow windows, through which the light filters, give life to the walls covered in frescoes; the light which enters through apertures in the drum illuminate the scene of the Creation painted on the dome. |

|

|

Eastern facade

|

| The internal spatial rhythms are projected to the

exterior by the articulated flowing of the facades. On the East facade (42,43) and on the

West facade (7, 8) two deep niches (46) have been carved in order to create a precise

chiaroscuro rhythm: both facades in fact have rather flat surfaces differing from the

Southern and Northern facades which are articulated with high-reliefs. All the facades

terminate with a tympanum, on which the low-relief figure of an evangelist is carved,

which coherently formulates the sloping roofing on each arm of the cross. The fulcrum of

the complex is the drum (rebuilt in the XIV century) richly decorated and surmounted by a

cone which enclosed the dome. Of the monasterial complex of Akdamar, other than the church of the Holy Cross (915-922), there are also a series of secondary buildings built in later centuries. Built on to the north-east side of the church, there is a small chapel or oratory, built perhaps by KatholikÚs Zaccaria (1296-1336): a barrel vault covers the internal space to which one has access through a door on the west side. A small doorway, also covered by a barrel vault, but built at a later date than the chapel, links it to the church of the Holy Cross. |

|

Low reliefs of the southern facade St. Stephen the Protomartyr, Sophonia the Prophet, another prophet, Elia the Prophet Below the scene where Jonah is thrown into the grasp of the fish; to the left is the fish; above Jonah is beside the king of the city Nineveh |

|

| There is also a gavit (6, 7) built in 1763 on the western side

of the church: a square space covered by a series of crossed vaulted arches with a

bell-tower doorway built in the XIX century. A few meters from the complex, towards the

south-east, there is a small chapel, today partly destroyed, dedicated to St. Stephen and

erected by KatholikÚs Stephen III (1272-1296) in 1293. One can deduce from the remains

that it consisted of a single space in the form of an apse, covered by a barrel vault,

with an entrance situated on the West side.

As a testimony of his fugitive existence, man brings life to stone, projecting on it a more or less defined unconscious meaning, his thoughts, his attitudes, or the most sublime Intuitions of the spirit, making them an integral part of the revelation: the link between him and God. Stone was widely used as a construction element in mediaeval times in Armenia in all sacred architectural expressions and to describe the architectural language as a prayer, used by man to glorify his eternity, and in the spatial continuity of the unification of sky and earth. In mediaeval times the Armenian superimposed the illuminated circle - (mandala) over the image of the cross, representing the four cardinal cosmic points, image of perfection, through which he succeeds in elaborating a series of theme variations to use in the designing of sacred buildings and also expressing a large range of aspects, ideas and emotions. It is on this plan, imagined in the shape of a cross on which he builds the walls, covering this microcosm with the gmbet (dome), and putting himself at the centre, where kneeling on this sacred centre - illuminated by the external light which converge here through appropriate openings, can contemplate the image of the resurrection and of the transformation of death to eternal life. Variations could be made by modelling the volume, the external surfaces and the internal space, covering the facades with high and low reliefs; he succeeds in showing the continuity of religious man - cosmos in the architecture! structure, creating a house of God for man, inserted and orientated according to his rhythms of life and places along his path. The only example in the field of mediaeval Armenian sacred architecture, is the architect and sculptor called Manuel, builder of the complex at Akdamar, who opposes the rigorous traditional logical instinct which guided the architectural style of the times. His mind tended towards the abstract and one opens oneself to a vision of the world based on relationships which reveal an existentialist need to discover what goes on behind the concrete sense, the pure concept, to find the hidden truth beyond the deceiving earth reality. It is for this reason that the task of building a palatine church, as an on the island eventual seat of the KatholikÚs of the town of Akdamar given to him by king Gagik, is the long awaited occasion to express himself, create his microcosm and tell the history of the Universe beginning from the Creation. He begins telling the story by carving on the exterior and painting frescoes on the interior of the building. Symbolism and abstraction are his most preferred instruments of narration: deciding to carve 153 figures in memory of the number of fish caught in miraculous fish tale. Manuel places the story of Genesis on the central part of the East facade, and he makes it into a central point where the story of humanity begins: Adam and Eve who embody birth, happiness and disaster, the nude body is pure in its humanity; the tree, the symbol of knowledge; the apple, the symbol of evil (mela = malum); and the seducing sin is represented by a serpent with four legs. On the West facade he carves King Gagik in the act of donation next to Jesus Christ while he accentuates the sacred character of the scene by the presence of two Seraphims, two angels, and by the Guardian angel; Jesus Christ has smaller dimensions than those of the king, whose halo around his head equally confirms the divine character attributed to him by the mediaeval tradition. On the east facade Manuel continues the theme of the Creation, he tells how Adam gave the name to the animals and describes the evangelisation of the country and of the whole world: under the figure of Adam a king (perhaps Gagik) is flanked by two nobles in the elevation of the lime - a fundamental mystery of the process of Intuition -, while seven angels, including the archangels Gabriel and Michel, are placed in different parts of the monument to suggest the resurrection: - ... and seven angel who had seven trumpets began to play them... - (Apocalypse VIll 6). The saints Theodore, George and Sergius are engaged in a battle between the cosmic forces of evil, represented in forms of dragons, panthers etc. The slender but illuminated force of David overpowers that of the gigantic Goliath, Jonah returns to rest after having liberated himself from the sea-monster, Samson kills and wins again and so on. Numerous personages and their stories, always referred to as strong men or a man-God who destroys the forces of evil and liberates his own people from destruction or death, nearly always surrounded by halos which represent the cosmos with its relationship to the Divine force. Manuel covers his scenes everywhere with animal figures, often, like a lion, the ox and the eagle, suggesting the symbol of the saints Mark, Luke, and John, however always seen in function with their universal and transcending essence. Nearly all the animals, both domestic and wild are represented: the lion on its own, symbol of pure strength, or in pairs, symbol of totality; the dog, being a noble animal, is the symbol of loyalty; rodents and fish, are symbols of depth; the birds, are symbols of the earthly existence as an intermediate passage towards immortality, and mystic animals, which sometimes symbolise the devil and at other times unite in a single body the symbolic significance of other animals, such as the serpent or the bird. In the decorative bands he creates a rich repertoire of symbols taken from nature and preferred by the Christian tradition, however, mixed in with the traditional scenes of people, where the activities (are brought into evidence) particularly significant of the various classes which made up the Armenian mediaeval society.

The dome, the drum and the East apse repeat in detail the Creation, while the frescoes of the minor apse under the balcony announce a second coming of Christ, encompassed by a solar wheel (symbol of totality); carved on the beam over the southern entrance is a seal which becomes absolute when flanked, as nearly always, by representations of bunches of grapes and pomegranates, which recall Christ's sacrifice, donator of his own blood for the ransom of humanity, a symbolism always maintained and even nowadays essential in man's religious rites. The paintings of the church of the Holy CrossMonumental painting was less extensively used in Armenia than in neighbouring countries. However, fragmentary remains in several VIIth century churches, parts of a large composition of the Last Judgement and of other paintings in the church of Tathev, built in 930, representations in other churches, as well as references in the works of the historians or in literary texts, are sufficient proof that this mode of church decoration was not alien to Armenian practice. The church of the Holy Cross at Akdamar is the only monument to have retained a substantial part of the paintings which once adorned the walls. In this respect, as well as through the rich sculptures of the facades, it is an outstanding monument of Armenian art. Moreover, through the contribution it brings to the study of church decoration during the Middle Ages, its significance transcends the limits of Armenia proper. But time and men have not dealt kindly with this church. The paintings of the area above the cornices have disappeared, except for fragmentary scenes around the drum of the dome; very little remains of the compositions on the lowest zone of the walls; in other sections a few scenes have been repainted at a later date. Nevertheless the main part of the decoration still remains, enabling us to recognise the general plan that had been adopted, and to study the style and the iconography of the individual scenes. The severe and hieratic style of the sculptures also characterises the paintings which are undoubtedly of contemporary date. The figures stand or are seated in frontal or three-quarter views. The attention is centred on the principal actor of the scene not through the compositional scheme, but because, being larger, it dominates over the secondary figures who are often massed In inverted perspective. The attitudes are static, even in those scenes which imply action. The linear schemes predominate in the rendering of the figures without any definite attempt to render the plasticity of the human form. Darker lines of the local colours, where the blues and browns predominate, delineate the folds of the draperies. All these traits tend to give an other-wordly character to these representations, to remove them into a sphere other than that of every day life, an impression enhanced by the rapt expression of the figures gazing into space. Thus, despite a certain degree of awkwardness, these paintings are strangely impressive. The sculptures of the exterior comprised several Old Testament scenes, but only individual figures of Christ, the Virgin and saints. Within the church, as is natural, the emphasis is no the Gospel scenes which decorate the exedrae, and on the numerous portraits of bishops painted in the niches and on the outer faces of the pilasters. But the Old Testament has not been entirely omitted. Vestiges of several scenes, from the introduction of Adam into the Garden of Eden to the expulsion of Adam and Eve, can still be seen on the drum of the dome. The episodes follow one another in a continuous frieze, that is according to a mode of decoration used during the Early Christian period. The presence of these Old Testament scenes has an additional interest, for it serves to illustrate the parallelism of the Old and the New Testament, propounded by the Armenian writers as well as by the Greek and Latin Church Fathers. The terrestrial paradise lost through the Fall appears in the dome, while the Gospel scenes painted below recall that paradise lost will be regained through the Incarnation and the Sacrifice of Christ. A large figure of Christ was probably represented in the conch of the apse, now covered with a uniform layer of paint. Below this area six apostles stand, holding the book of the Gospels. The other six were probably represented on the adjoining piers or on the lower zone of the apse. The extensive Gospel cycle, including minor episodes of the life of Christ, begins on the south side of the church, and it is developed, on three registers, in the exedrae and occasionally on the piers. In several instances there is hardly any separation between the individual scenes so that we have, in effect, a continuous frieze, girding the church on three sides, interrupted only by the niches and by the windows. The infancy scenes occupy the south and west exedrae. The Annunciation, where the Virgin is seated arms raised in the attitude of the orans, is followed by the Visitation. The Nativity entirely fills the area to the right of the central window. The composition, with Mary and Joseph seated on either side of the manger, retains the iconographic scheme familiar through representations of the Early Christian period, but in accordance with the general practice in Armenian art, the shepherd and the Magi bringing their gifts have also been represented. The Gospel narrative continues on the west exedra with Joseph's dream, the Flight into Egypt, and the Massacre of the Innocents. This last scene has been greatly developed. Two groups of men stand in front of the large enthroned figure of Herod giving his orders; the massacre itself occupies the extreme right corner of the exedra while beyond, on the face of the adjoining pier, six bereaved mothers stand, in a dignified attitude, only their sad eyes expressing their sorrow. The Baptism, the Transfiguration and the Marriage Feast at Cana occupy the north exedra. The painter has modified the chronological sequence of the events in order to place in a central position the Transfiguration which took place after the Marriage at Cana. The large figure of the transfigured Christ acquires even greater prominence by being painted immediately above the window. The inclusion of the wedding feast in this exedra has also a theological significance: the first miracle through which Christ's divine power became manifest to the disciples is thus grouped with the first two theophanies, those of the Baptism and the Transfiguration. However in the actual representation of the scene the secular elements are stressed in preference to the miracle itself. Christ remains seated at the table while the master of the feast watches the servant pouring the water into a basin. To the right two young men are seated on the ground, holding wine glasses, the one who is crowned probably representing the bridegroom. If this section has not been repainted, we have here the first example of the type of composition favoured later by the miniaturists of the province of Vaspurakan, and which differs from the usual iconographic scheme. The king's gallery being built in the south exedra, the Gospel narrative is resumed on the second zone of the west exedra. The four scenes proceeding the Passion, represented here, comprise each a large number of figures, the compositions are thus crowded together, with no separation between them. In the Raising of Lazarus Christ, accompanied by His disciples massed on three tiers, stands next to the shrouded figure of Lazarus, erect in a rectangular frame suggesting the sepulchre. The two sisters are seen above the sepulchre; one of them points to Lazarus while gazing at Christ. In the Entry into Jerusalem Christ, seated frontally on the ass, is welcomed by five children who spread their garments under the ass's feet. Behind the apostles, figured on four rows, one can see the roof of a large building representing Jerusalem. Two large buildings and a ciborium also fill the background of the next two compositions, exceptionally suggesting that the event takes place inside the house. The first scene is based on John's account of the supper at the house of Lazarus, when Martha served Jesus and Mary anointed His feet, rather than on that of Christ's anointment by Mary Magdalene, for both sisters are included in the composition. The second scene represents the Washing of the Disciples' Feet. The juxtaposition of these two events brings to the fore the parallelism recalled in the ritual of Maundy Thursday in the Armenian church. During the afternoon service, when the celebrant, bishop or priest, blesses the oil and the water with which he will wash the feet of the clerics, he recalls Christ's anointment adding that it is in memory of that event that the oil is blessed. It is also significant that the scene of Christ's anointment, hardly ever represented in monumental art, has been selected in preference to the Last Supper, one of the major scenes of the Gospel cycle. The badly damaged composition of Christ before Pilate, painted on the pier, leads to the Passion and Resurrection scenes of the north exedra. The large figure of Christ, erect on the cross, dominates the composition of the Crucifixion; the two robbers, their hands tied behind their back, are represented in a smaller scale. As in the early examples of this scene Christ wears a long, sleeveless garment. Two medallions, framing the allegorical figures of the sun and the moon, are painted at the sides of the semicircular bands suggesting the arc of heaven. The lance-bearer, Longinus, is exceptionally an elderly man, wearing a chlamys and a helmet, a costume that suggests a confusion with the centurion, as in apocryphal life of Longinus. The sponge-bearer is, as usual, a young men in a short tunic; the vessel with the vinegar stands on the ground next to him. Through lack of space, the Virgin, one of the holy women and the apostle John have been relegated to the lower part of the composition, next to the mound on which the cross is raised. Three different scenes recall the Resurrection. The first one represents the Visit of the holy women and of the apostles Peter and John to the sepulchre. The angel, seated in a hieratic attitude, gazes directly in front of him, instead of a speaking to those who had come to the tomb. His wings, raised vertically, form a triangular motif which re-echoes the shape of the roof of the sepulchre. The latter is an imposing structure with a lattice-work grill between the columns, as in the earliest representations of this scene, but the acanthus leaves, framing the conical roof, give to it an appearance similar to that of the tempietto painted in Armenian manuscripts of the Xth century. The large stone, in front of the door, is covered with a cloth decorated with three crosses, for the - rolled stone - of Christ's sepulchre was used as an altar in Jerusalem, on special occasions. The second Resurrection scene is that of the Harrowing of HeH or Descent into limbo. Christ, carrying the large, double cross, and exceptionally accompanied by two angels, advances toward Adam and Eve and bends slightly to seize Adam's hand. There remain only faint traces of the righteous who usually are included in this scene. The Resurrection cycle ends with Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene and the other Mary. The text of Matthew 28:9, - and they came and held him by the feet and worshipped him -, written next to the figures, and which I have now been able to decipher entirely, shows that I was mistaken in my earlier Hypothesis, when I thought that King Gagik may have been included in this composition. The two figures are those of the holy women: one standing, hands raised, opposite Christ; the other kneeling at His feet. There are but slight remnants of the paintings of the lowest zone. In the west exedra, the representation of Christ seated in a mandorla borne by flying angels is assuredly the upper part of the Ascension. The faint traces of nimbed figures in the right half of the same exedra may be part of the Pentecost scene. On the extreme right of the north exedra, where the cycle ended, one can see the bust of a woman in front of a building. One can therefore surmise that the Dormition of the Virgin had been represented here, for several representations of this scene include the friends of Mary watching from the windows. As already mentioned the king's gallery left little room for paintings in the south exedra, except in the upper zone, but a large composition had been represented in the conch above the south door. This composition has been disfigured and partly obscured by layers of later paintings. However, one can still see part of the original work: the bust of Christ, in the upper part, and two rows of nimbed figures below. The general scheme of this composition recalls that of the miniatures in two Byzantine manuscripts of the IXth century representing the Second Coming of Christ. There is a still closer connection with an Armenian sculpture of the XIth century. On one the slabs decorating the octagonal drum of the gavit or zamatoun of the church of Saint John, at Horomos, erected in 1038, Christ is figured in majesty, seated on a throne surrounded by the symbols of the four evangelists; below are two rows of nimbed men. At Akdamar, as at Horomos, the composition represents an early iconographic type of the Last Judgement, with only the images of the righteous. The cycle of paintings, which began with the Annunciation in the south arm of the church, thus ends also on the south side with the evocation of Christ's Second Coming.

The conservative character of Armenian art comes to the fore in several compositions where the iconographic types of the Early Christian period have been retained. But minor, though significant differences show the personal contribution of the painters, and the appearance of types of representations which will be in great favour, later, among the miniaturists of this province. One final point should be stressed. Though stylistically related to the sculptures, and the work of the same group of artists, the paintings in no way repeat the sculptures of the facades. We have thus a very rich repertoire bringing a valuable contribution to the study of church decoration in the East Christian world.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Our Hotel | Turkey | Cappadocia | Daily Tours | Views | Guestbook | Request Form | Home |

|