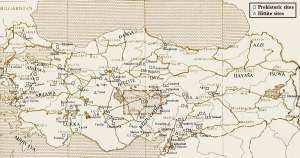

THE PREHISTORIC PERIOD

Anatolia was the birthplace of some of the earliest civilizations of

mankind. The first traces of agriculture were found in southern Middle Anatolia, to the

west of Cappadocia, in the aceramic period at Hacılar,

c. 7040 BC. according to carbon 14 dating. The Çatalhöyük settlement, located in the

eastern part of the same region and founded in approximately 6500 BC., stands out as an

unrivalled prehistoric centre of culture. It was here that man created some of the first

great works of art. The most important achievements are the mural paintings and painted

reliefs which adorned the walls of the houses and cult rooms. Some of these are now

exhibited in the Ankara Museum.

The shrines were situated in the centre of a complex of four to five

houses, usually consisting of one large room. Neither the houses nor the shrines had

doors. Access was from the roof by means of wooden ladders. These buildings were built of

mud-brick and had small windows set high up under the eaves. Each living room had at least

a bench made of mud-brick, which served as a divan, work-table and bed. Beneath this bench

the dead were buried after the flesh had been removed from their bodies. These graves

contained beautiful burial gifts, such as the magnificent obsidian mirror found in one of

the houses. In a shrine from Level VII a mural painting (c. 6200 BC. by carbon dating) was

found which apparently represents the eruption of a volcano, possibly the nearby Hasan Dağ, lying in western Cappadocia and superbly dominating the

plateau around the Tuz Gölü and Aksaray.

This is the earliest known landscape painting in history. Particularly favored among the

myriad themes of the polychrome mural paintings were hunts, dancers and acrobats and above

all paintings of a religious and funerary character. Some houses contained a strikingly

large number of bulls' heads or horns mounted in rows along the walls or attached to the

sides of the benches, as can be seen in a restored room in the Ankara Museum.

These no doubt represented the male deity; for the husbandman of

Anatolia the bull was not only a symbol of strength but, more important still, the

progenitor of the horned cattle without which they could not cultivate their land. This

explains why, after agriculture first began in Anatolia, the male god was depicted in the

shape of a bull. This practice persisted until the Hittite era, as is seen in an orthostat

relief from Alacahöyük in which a king is represented

venerating a bull that stands on an altar. The main deity was, however, the great Mother

Goddess, who appears in human form on a painted stucco relief from Çatalhöyük. She too

is sometimes represented by her wild beasts. The beautiful, richly colored stucco relief

of two leopards which adorned the walls of one of the shrines in Level VI at Çatalhöyük

(c. 6000 BC.) may be assumed to represent the mighty goddess. A statuette depicting the

goddess seated on a throne supported on two felines indicates that leopards were in fact

her attributive animals. The goddess is about to give birth to a child, a typical posture

and frequent motif of the Hacılar clay figurines.

The earliest earthenware vessels in Anatolia were made in the first

Çatalhöyük period, c. 6500 BC. Beginning with the simple monochrome articles of the

Neolithic period, they gradually evolved into the magnificent pottery of the Late

Neolithic and Early Chalcolithic eras. In the upper two habitation levels at Hacılar (c.

5400-5250 BC. by radiocarbon dating) painted vases have been brought to light which are of

unrivalled beauty and appeal.

In Cappadocia the most important place for the Aceramic neolithic

period is Aşıklıhöyük.

|