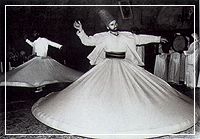

Whirling Dervishes

Whirling Dervishes

Islamic

mysticism seeks awareness of god in manner being, and hence the various

mystic sects o tarikats of dervishes or sufis have generally been

characterized by open-mindedness, vision, exuberance and lot of the

arts, particularly music and poetry. Their tendency to relegate doctrine

and the outer forms of worship a secondary degree of importance has

frequently brought the sects into conflict with orthodoxy over the

centuries The emphasis on dance

music of the Mevlevi’s, and the transgression of the orthodox

ban on intoxicating liquor by the Bektaşis are issues which were strongly

condemned by the Muslim establishment during Ottoman times in Turkey. Islamic

mysticism seeks awareness of god in manner being, and hence the various

mystic sects o tarikats of dervishes or sufis have generally been

characterized by open-mindedness, vision, exuberance and lot of the

arts, particularly music and poetry. Their tendency to relegate doctrine

and the outer forms of worship a secondary degree of importance has

frequently brought the sects into conflict with orthodoxy over the

centuries The emphasis on dance

music of the Mevlevi’s, and the transgression of the orthodox

ban on intoxicating liquor by the Bektaşis are issues which were strongly

condemned by the Muslim establishment during Ottoman times in Turkey.

The first Islamic sect emerged in Yemen and dates from the 37th

year of the Hegira (657 AD) when the Angel Gabriel is supposed to

have exhorted Üveys el-Karani to turn his back on the material world

and choose a life of asceticism. Each mystic sect by tradition also

asserts legitimacy by tracing its origins to Ali or Ebubekir Cüneyd-I

Bağdadi (died 910) and other sufis forged a link between the concept

of bezm-i elest (the union of God and souls) and the ecstatic dance

known as sema

introducing various recited litanies in praise of God to the accompaniment

of whirling movements. Experts in Muslim jurisprudence have frequently

rejected sects such as the Rufais, Halvetis and Mevlevi’s on

the grounds that dancing degrades religion. In the early 16 th century

, for instance, Ibn Kemal (d. 1534) wrote a treatise entitled Risaletün

fi Tahkik'r-Raks asserting that music and spinning movements

know as devran were sinful, citing early fetva as evidence for his

argument, Ebussuud efendi (d.1574), on the other hand, while still

disapproving, took the view that with certain modifications and restrictions

the practice should be tolerated.

Many

of the sects which arose in Anatolia, such a Yessevis, Bektaşis and

Nakşis fell foul of orthodox although the Mevlevi’s commanded

the gruding respect of the othodox establishment largely on account

of the Mesnevi, the greatest philosophical work of Mevlana Celaleddin-I

Rumi, a Turkish Sufi who migrated from northern Persia to Anatolia

in the 13th century. The sed which grew up after his death

is by far the most fascinating in terms of dervish culture, including

ritual and costume Many

of the sects which arose in Anatolia, such a Yessevis, Bektaşis and

Nakşis fell foul of orthodox although the Mevlevi’s commanded

the gruding respect of the othodox establishment largely on account

of the Mesnevi, the greatest philosophical work of Mevlana Celaleddin-I

Rumi, a Turkish Sufi who migrated from northern Persia to Anatolia

in the 13th century. The sed which grew up after his death

is by far the most fascinating in terms of dervish culture, including

ritual and costume

The sema of the Mevlevi’s differed from the movement adopted

by other sects. The dervishes turned independently, without touching

shoulder to shoulder, both around their own axis and around the sheikh

and other dervishes. They made neither a sound no any movement of

the hands arms or head The Mevlevi novice underwent long years of

self-denial, penance and training in the sema The state of trans which

the sema induced cut off all awareness apart from that of communion

with God. The Bektaşis, however ridiculed the Mevlevi dance as an

unnecessary adjunct to the worship of God. Mevlana(d. 1273) believed

that the spirit was relieved of the weight of the flesh in the course

of the sema, and that the jubilation which emanated from man2s true

being as sense and thought could only be experienced in this way.

Although the sema could be practiced singly, it was customary for

the dervishes to perform the sema together at noon in the semahane

or hall of dergah. The dervish responsible for the ritual would spread

the sheepskin which symbol ised the office of the sheikh, head of

the convent, on the floor of the semahane. Wearing their white costumes

with voluminous skirts known as tennure and tall hats, the dervishes

would perform their prayers when the sheikh warning a green headdress

appeared. After readings from the Mesnevi and the Koran, one of the

dervishes would begin to play the ney, a reed flute of great antiquity

whose plaintive music is associated almost exclusively to the Mevlevi

sect.

Lord Charlemont, who traveled in Turkey in 1749 gave the following

account of the Mevlevi ceremony, which was performed in public on

Tuesdays and Fridays to an audience which included many women.

The

crowd pressed toward the extremities of the chamber, which was occupied

by the monks dressed, as usuand in a gown of coarse whitish cloth,

close before and behind, and fastened about the was it with a leather

strap. Over this they wore a sort of jacket… On their heads

they wore caps of the same color, usually made or camel's hair,

and stiffened into the form of sugar-loaf (The prayer) was succeeded

by a long hymn, performed with great vociferation, and to our prejudiced

ears, with little music, and accompanied by a sort of flute or baut

bois and by a large tabor like a small kettle-drum. As soon as the

hymn was ended, the instruments changed their tune into something

of a quicker movement, and the monks began to turn themselves round

with a velocity not to be described or easily conceived. Our most

fixed attention could not count the number of their revocations,

but according to our best reckoning, they must have exceeded sixty

in one minute. This painful exercise was continued for a considerable

time, till at length the music ceased, and they stopped seemingly

undisturbed by giddiness, and thus the ceremony ended. The

crowd pressed toward the extremities of the chamber, which was occupied

by the monks dressed, as usuand in a gown of coarse whitish cloth,

close before and behind, and fastened about the was it with a leather

strap. Over this they wore a sort of jacket… On their heads

they wore caps of the same color, usually made or camel's hair,

and stiffened into the form of sugar-loaf (The prayer) was succeeded

by a long hymn, performed with great vociferation, and to our prejudiced

ears, with little music, and accompanied by a sort of flute or baut

bois and by a large tabor like a small kettle-drum. As soon as the

hymn was ended, the instruments changed their tune into something

of a quicker movement, and the monks began to turn themselves round

with a velocity not to be described or easily conceived. Our most

fixed attention could not count the number of their revocations,

but according to our best reckoning, they must have exceeded sixty

in one minute. This painful exercise was continued for a considerable

time, till at length the music ceased, and they stopped seemingly

undisturbed by giddiness, and thus the ceremony ended.

Galata Mevlevihane, the dervish convent visited by Charlemont, was

one of Istanbul’s most distinguished centers of music and literature

until the turn of the 20th century. Many major Turkish

composers, calligraphers and poets trained here. Foremost among them

was the scholar and poet Şeyh Galip (1757-1799), who under the patronage

of Sultan Selim III and his sister Beyhan Sultan became şeyh of the

dergah.

The

Mevlevi dervishes had lodges in many parts of Turkey, including Afyon,

Kütahya, Bursa, Gelibolu, Aleppo, and of

course Konya the home of Mevlana. In İstanbul

there were Mevlevi lodges at Kulekapısı, Bahariye in Beşiktaş, Kasımpaşa

and Üsküdar. They all consisted of a large inner courtyard surrounded

by the semahane, a room for the novices, reception rooms, a harem

where the family of the sheikh lived, refectory, and kitchen. Day

began with morning prayers and meditation, and continued with study

of Mevlana's writings, and then music practice on the ney and kudüm,

a small double drum played with small sticks. Although Charlemont

referred to the dervishes as monks, the resemblance is only slight,

since dervishes married, kept their own homes, and made their own

livings. The

Mevlevi dervishes had lodges in many parts of Turkey, including Afyon,

Kütahya, Bursa, Gelibolu, Aleppo, and of

course Konya the home of Mevlana. In İstanbul

there were Mevlevi lodges at Kulekapısı, Bahariye in Beşiktaş, Kasımpaşa

and Üsküdar. They all consisted of a large inner courtyard surrounded

by the semahane, a room for the novices, reception rooms, a harem

where the family of the sheikh lived, refectory, and kitchen. Day

began with morning prayers and meditation, and continued with study

of Mevlana's writings, and then music practice on the ney and kudüm,

a small double drum played with small sticks. Although Charlemont

referred to the dervishes as monks, the resemblance is only slight,

since dervishes married, kept their own homes, and made their own

livings.

- See also:

-

Photos

of Whirling Dervishes and

Photos

of Sema dancing in Hacibektas

|