The Oldest Map of the World

DATE:

6200 B.C. DATE:

6200 B.C.

LOCATION: Museum at Konya, Turkey

The human activity of graphically translating one's perception of his world is now

generally recognized as a universally acquired skill and one that pre-dates virtually all

other forms of written communication. Set in this pre-literate context and subjected to

the ravages of time, the identification of any artifact as "the oldest map", in

any definitive sense, becomes an elusive task. Nevertheless, searching for the earliest

forms of cartography is a continuing effort of considerable interest and fascination.

These discoveries provide not only chronological benchmarks and information about

geographical features and perceptions thereof, but they also verify the ubiquitous nature

of mapping, help to elucidate cultural differences and influences, provide valuable data

for tracing conceptual evolution in graphic presentations, and enable examination of

relationships to more "contemporary primitive" mapping.

As

such, there are a number of well-known early examples which appear in most standard

accounts of the history of cartography. The most familiar artifacts presented as "the

oldest extant cartographic efforts" are the Babylonian maps engraved on clay tablets.

These maps vary in scale, ranging from small-scale world conceptions to regional, local

and large-scale depictions, down to building and grounds plans. In detailed accounts of

these cartographic artifacts there are conflicting estimates concerning their antiquity,

content and significance. Dates quoted by "authorities" may vary by as much as

1,500 years and the interpretation of specific symbols, colors, geographic locations and

names on these artifacts often differ in interpretation from scholar to scholar. As

such, there are a number of well-known early examples which appear in most standard

accounts of the history of cartography. The most familiar artifacts presented as "the

oldest extant cartographic efforts" are the Babylonian maps engraved on clay tablets.

These maps vary in scale, ranging from small-scale world conceptions to regional, local

and large-scale depictions, down to building and grounds plans. In detailed accounts of

these cartographic artifacts there are conflicting estimates concerning their antiquity,

content and significance. Dates quoted by "authorities" may vary by as much as

1,500 years and the interpretation of specific symbols, colors, geographic locations and

names on these artifacts often differ in interpretation from scholar to scholar.

One such Babylonian clay tablet that has been generally accepted as "the earliest

known map" is the artifact unearthed in 1930 at the excavated ruined city of Ga-Sur

at Nuzi [Yorghan Tepe], near the towns of Harran and Kirkuk, 200 miles north of the site

of Babylon [present-day Iraq]. Small enough to fit in the palm of your hand (7.6 x 6.8

cm), most authorities place the the date of this map-tablet from the dynasty of Sargon of

Akkad (2,300-2,500 B.C.); although, again, there is the conflicting date offered by the

distinguished Leo Bagrow of the Agade Period (3,800 B.C.). The surface of the tablet is

inscribed with a map of a district bounded by two ranges of hills and bisected by a

water-course. This particular tablet is drawn with cuneiform characters and stylized

symbols impressed, or scratched, on the clay. Inscriptions identify some features and

places. In the center the area of a plot of land is specified as 354 iku [about 12

hectares], and its owner is named Azala. None of the names of other places can be

understood except the one in the bottom left comer. This is Mashkan-dur-ibla, a place

mentioned in the texts from Nuzi as Durubla. By the name, the map is identified as of a

region near present-day Yorghan Tepe (Ga-Sur at the time, the name Nuzia 1,000 years

later), although the exact location is still unknown. Whether the map shows a stream

running down a valley to join another, or running from that to divide in to three, and

whether they are rivers or canals, cannot be determined. The shaded area at the left side,

to or from which the channels run, was named, but the writing is illegible. Groups of

overlapping semicircles mark ranges of hills, a convention used by artists then and in

later times. The geographic content consists of the area of a river valley which may be

that of the Euphrates flowing through a three-lobed delta and into a lake or sea in the

northern part of Mesopotamia. Also shown on this tablet may be the tributary river the

Wadi-Harran, the Zargos Mountains in the east, the Lebanon, or Anti-Lebanon in the west,

and cities which are symbolized by circles. North, East and West are indicated by

inscribed circles, implying that maps were aligned in the cardinal directions then as they

are now. This tablet also illustrates the sexagesimal system of mathematical cartography

developed by the Babylonians and represents the earliest known example of a topographic

map.

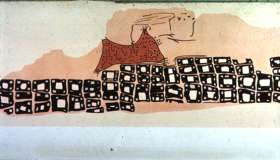

However, while the Babylonian clay tablet map described here has been the generally

accepted "earliest known map", another contender might be the cartographic

artifact found in 1963 by James Mellaart in Ankara, Turkey during an excavation of

Çatalhöyük in Anatolia. While less distinctive and on a much larger scale, this

unearthed map-form is a wall painting that is approximately nine feet long and has an in

situ radiocarbon date of 6,200 + 97 B.C. Mellaart believes that the map depicts a town

plan, matching Çatalhöyük itself, showing the congested "beehive" design of

the settlement and displaying a total of some 80 buildings. One illustration of this map

shows the painting from the north and east walls of the shrine. In the foreground is a

town arising in graded terraces closely packed with rectangular houses. Behind the town an

erupting volcano is illustrated, its sides covered with incandescent volcanic bombs

rolling down the slopes of the mountain. Others are thrown from the erupting cone above

which hovers a cloud of smoke and ashes. The twin cones of the volcano suggest that an

eruption of Hasan Dağ, rising to a height of 10.672 feet, and standing at the eastern end

of the Konya Plain and visible from Çatalhöyük, is recorded here. These local volcanic

mountains were important to the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük as a source of obsidian used

in the making of tools, weapons, jewelry, mirrors and other objects. Further, from graphic

embellishments around the mountain, Mellaart has speculated that the depiction of the

volcano in an active state is accurate since vulcanism in this area continued for some

4,000 years later.

Clearly, the Çatalhöyük "map" is still not the beginning of cartographic

history. Investigation into the earliest beginnings of cartography will continue with a

fair probability of further successes. This optimism is warranted by the fact the the

materials used during these periods to record such geographical spatial concepts were more

durable elements such as stone, clay, metal, earthenware, etc., unlike later cartographic

artifacts made of more fragile materials such as paper and wood.

|