The Art of Turkish Carpet Weaving

Carpets

discovered in excavations of tombs at Pazarık have proved that the ancient Turks wove

carpets using the complex Gördes knot technique as early as the Hun period. However,

researchers then encounter an unexplained gap until the fragments of 3rd and 6th century

carpets made using a simple weft knot discovered at the turn of this century at Lou-Lan

west of Lake Lop in Eastern Turkistan. Possibly the sophisticated technique of the

Pazarık carpet had been forgotten over the intervening centuries, and the process of

evolution began all over again with the discovery of a simple knot. When we come to

Islamic times, we find among the Abbasid carpet fragments with geometric designs some

found at Fostat (old Cairo)whose knotting technique resembles that of Eastern Turkistan. Carpets

discovered in excavations of tombs at Pazarık have proved that the ancient Turks wove

carpets using the complex Gördes knot technique as early as the Hun period. However,

researchers then encounter an unexplained gap until the fragments of 3rd and 6th century

carpets made using a simple weft knot discovered at the turn of this century at Lou-Lan

west of Lake Lop in Eastern Turkistan. Possibly the sophisticated technique of the

Pazarık carpet had been forgotten over the intervening centuries, and the process of

evolution began all over again with the discovery of a simple knot. When we come to

Islamic times, we find among the Abbasid carpet fragments with geometric designs some

found at Fostat (old Cairo)whose knotting technique resembles that of Eastern Turkistan.

A wool carpet fragment bearing a palmette motif on a red ground and worked in Gördes

knots (named after the Turkish carpet weaving centre of Gördes and alternatively known as

the Turkish knot), found at Fostat and now in Cairo's Museum of Islamic Art marks the

beginning of knotted carpet making in the mediaeval Islamic world. It is thought that this

carpet must have been exported from Western Turkistan between the 7th and 9th centuries.

Another fragment in Berlin Museum of Islamic Art may have been imported from Western

Turkistan, perhaps Bukhara to Egypt. Since there are no other contemporary fragments from

that region for comparison, we can not say more.

The

other carpet fragments discovered in Egypt are made in the single warp knot technique of

Eastern Turkistan, and the dominant ground color is dark blue. These fragments are now in

the Benaki Museum in Athens. The

other carpet fragments discovered in Egypt are made in the single warp knot technique of

Eastern Turkistan, and the dominant ground color is dark blue. These fragments are now in

the Benaki Museum in Athens.

Anatolian Turkish carpets dating from the 13th century found in Konya are woven in the

Gördes knot. These carpets are the earliest for which provenance and dating involve no

speculation. The discovery of eight Turkish Seljuk carpets by F. R Martin in Alaeddin

Mosque in Konya in 1905, was followed by three more Seljuk carpets found by R. M.

Riefstahl in 1930, and seven small carpet fragments found in Fostat in 1935-1936.

The art of carpet weaving was introduced to the Islamic world by Turkish tribes

migrating from Central Asia, and the single-warp knot spread as far as Spain. Carpets from

Turkey were highly valued in Europe where they became a popular accessory in paintings.

The introduction of animal figures into 14th century Turkish carpets parallels the

vigorous use of animal designs in many other branches of Seljuk art. These carpets were

already being exported to Europe, as pictures of Seljuk period Turkish carpets in European

paintings of this period indicate. Original examples of these carpets bearing animal

figures were not discovered until centuries later, however, in Konya, Istanbul and Fostat.

Following

the three Seljuk carpets which R. M. Riefstahl found in Beyşehir, he found a fourth large

15th century carpet which was the prototype of the so-called Holbein carpets, representing

another phase in the development of Turkish carpets. Following

the three Seljuk carpets which R. M. Riefstahl found in Beyşehir, he found a fourth large

15th century carpet which was the prototype of the so-called Holbein carpets, representing

another phase in the development of Turkish carpets.

These carpets were represented in paintings by Italian and later Flemish and Dutch

artists between the mid 15th and 16th centuries, but became known as Holbein

carpets because they appeared most frequently and in greatest detail in paintings by this

artist. They feature borders with an interlaced design inspired by the kufic Arabic

script, and a field of geometric designs enhanced by highly stylized floriate motifs. They

mark the beginning of a new Ottoman Turkish style of carpet design. The 16th century saw

the rise of a new and brilliant period in Turkish carpet weaving corresponding to the

classical period in Ottoman architecture and other arts. Carpets made in the Uşak region

mark the commencement of this development with an extraordinary diversity of motif and

composition which still await detailed study. Uşak carpets can be divided into two main

types, those with medallions and those with a design of stars but variations on these two

themes employ an immense repertoire of motifs. The medallion carpets were often conceived

as an infinite repeating pattern by placing halved medallions in the four corners around

the central medallion.

The medallion itself is a motif inspired by book binding and illumination of the

practiced by the carpet weavers of Tabriz, but now combined with the idea of infinite

repetition typical of Turkish carpets. Instead of retaining the principles of composition

applicable to the arts of the book, Turkish designers were guided entirely by the rules

and characteristics of the textile medium in which the weavers worked.

Star Uşak carpets display the principle of infinite repetition even more prominently,

this effect being achieved by arranging small medallions in the form of eight pointed

stars and diamonds in offset rows.

This type is smaller in size than the medallion carpet. Production of star Uşaks

continued for only two centuries, disappearing by the end of the 17th century, while the

medallion Uşak carpets continued to be woven until the mid-18th century.

In the late 16th century, an entirely different type of Turkish carpet, new both in

technique and its predominantly naturalistic motifs, emerged alongside the classic Turkish

carpet. Known as the Ottoman court carpet, it employed the Persian rather than Turkish

knot. The Persian knot, also called the asymmetrical knot, allows a finer, velvet like

texture to be created. Naturalistic motifs appear simultaneously in all other Turkish arts

at this time, with a profusion of tulips, hyacinths, roses, blossom, and curved leaves.

This style continued to evolve until the end of 18th century.

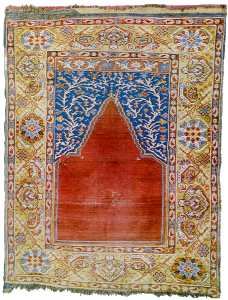

Ottoman

court prayer rugs were made in the Gördes, Kula, Ladik and Uşak tradition during the

18th century. A magnificent prayer rug known to have belonged to Ahmet I

(1603-1617) in Topkapı Palace Museum is still clearly worthy of a sultan, despite the

burns caused by a brazier being placed on top of it. Another court prayer rug in Berlin

Museum has a chronogram in the border giving the date 1019 (1610). Ottoman

court prayer rugs were made in the Gördes, Kula, Ladik and Uşak tradition during the

18th century. A magnificent prayer rug known to have belonged to Ahmet I

(1603-1617) in Topkapı Palace Museum is still clearly worthy of a sultan, despite the

burns caused by a brazier being placed on top of it. Another court prayer rug in Berlin

Museum has a chronogram in the border giving the date 1019 (1610).

The oldest known prayer rugs to have survived date from the 15th century, and

constitute a distinct category of Turkish carpets. Three of these in the Museum of Turkish

and Islamic Art in Istanbul feature completely different compositions, which indicates

that this was a period when innovation and creativity were given free rein. Other 15th

century prayer rugs can bee seen in Renaissance period paintings by the Bellinis,

Corpaccio and Lotto. Giovanni Bellini's portrait of Duke Loredan of Venice dated 1507 in

the Munich Gallery shows a prayer rug identical to one in the Berlin Museum of Islamic

Art. Another early example can be seen in a painting by Gentile Bellini hanging in the

National Gallery in London.

The

serrated lappet on the Bellini prayer rugs is replaced by a large palmette on the lower

edge of a magnificent early 16th century Uşak carpet in Berlin Museum. Another Uşak

carpet dated 1600 in the Bode collection is among the first examples of the double mihrap

niche rugs with a central medallion and an unusually broad border. Unfortunately very few

prayer rugs dating from the 15th and 16th centuries have survived, but the number and

variety rises sharply for the 17th century, when we find Gördes prayer rugs with curved

niches closely style rugs. Kula prayer rugs are distinguished by plainer niches and up to

ten narrow borders. There is also a type known as landscape Kula, with designs of

cottages and trees. The

serrated lappet on the Bellini prayer rugs is replaced by a large palmette on the lower

edge of a magnificent early 16th century Uşak carpet in Berlin Museum. Another Uşak

carpet dated 1600 in the Bode collection is among the first examples of the double mihrap

niche rugs with a central medallion and an unusually broad border. Unfortunately very few

prayer rugs dating from the 15th and 16th centuries have survived, but the number and

variety rises sharply for the 17th century, when we find Gördes prayer rugs with curved

niches closely style rugs. Kula prayer rugs are distinguished by plainer niches and up to

ten narrow borders. There is also a type known as landscape Kula, with designs of

cottages and trees.

Ladik prayer rugs are noted for their soft wool and glowing colors and are

characterized by rows of long stemmed tulips below or above the prayer niche. Those of Kırşehir and Mucur have niches with double or triple

outlines and their color schemes include two or three tones of red. With their vivid and

brilliant colors, Milas prayer rugs preserve the forms of Gördes prayer rugs with the

additional influences of Uşak and Bergama rugs.

Turkish carpet weaving continued to develop through to the end of nineteenth century,

and still survives today in Konya, Kayseri,

Sivas, Kırşehir, Isparta, Fethiye, Döşemealtı, Balıkesir, Yağcıbedir, Uşak, Bergama, Kula, Gördes, Milas, Çanakkale, Ezine, Kars and Erzurum. Enormous efforts

being made to prevent the art of carpet weaving falling into decline are meeting with

considerable success in many areas of Turkey today. |